By Brig. Zahir Ul Haider Kazmi

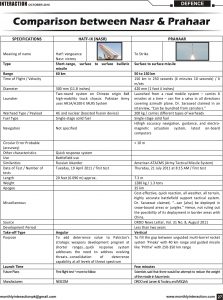

This part is a collection of declared specifications and assessments made on Nasr and Prahaar ballistic missile systems. A technical and technological assessment of these systems would assist in ascertaining their effect on the stability of deterrence between Pakistan and India. Incidentally, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) Directorate issued a prompt, short and rather ambiguous press release after the first flight test of Nasr. In obvious contrast, India flight-tested Prahaar on 21 July 2011 and a delayed, though less ambiguous, official statement appeared on the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) website in August 2011. Other details on the test were, however, instantly available in the Indian media. This degree of ambiguity about the results of missile flight-tests is understandable as the states do it to maintain technological advantage and to hide operational details that might reveal the trajectory of progress.

Experts were quick to amplify the officially released information on the Nasr flight-test to make technical and other assessments. While Nasr remains in the spotlight, there was muted response or analysis on the implications of the Prahaar test. The Western assessments on Nasr carried strains of disbelief in the technological feat of miniaturising a warhead that could fit into a missile of about 300-mm diameter. Since primary sources and academic work on Nasr and Prahaar is scant, all available information has been considered for a swift content analysis of both weapon systems. Unlike Pakistan’s prompt press statement, within hours of flight-test, Indian official and measured stance appeared on the DRDO website a month after the test. Before that, the Indian media carried excerpts of the statements made by Dr. VK Saraswat, DG, DRDO, and other unnamed scientists. By then several experts had vented all their intellectual steam against Nasr’s test and were probably not inclined to critically evaluate Prahaar by reconsidering their expressed positions. A gist of the DRDO statement and other statements on Prahaar is given below:

DG Indian Artillery also witnessed the test besides others. Developed in a short span of less than two years support from Indian industry and quality assurance agency MSQAA… will be the battlefield support system for the Indian Army: cost-effective, quick reaction, all weather, all terrain, and highly accurate battlefield support tactical system…Diameter 420 mm…length 7.3 meter…Range 150 km…apogee 35 km…time of flight 4 minutes and 10 seconds…weight 1280 kg…single-stage solid propulsion system…payload 200 kg (carries different types of warheads…terminal accuracy is (high accuracy navigation, guidance, and electro mechanical actuation systems, latest onboard computers) …the road mobile system carries 6 missiles at a time…can fire a salvo in all directions covering entire azimuth plane.

Some additional information that appeared in the media coverage immediately after the flight test is also worth noting. Prahaar “has high manoeuvrability and excellent impact accuracy.” The missile has a quick reaction time of launch “within a few minutes.” Dr. Saraswat, who is also scientific adviser to the Indian defence minister, said: It is an all-weather missile that can be launched from canisters. Since it can be fired from a road mobile launcher, it can be quickly transported to different places. It can be deployed in various kinds of terrain such as snow-bound areas or jungles…after a couple of more flights; we will be ready for production. The short-range missile would fill the gap “between unguided multi-barrel rocket system Pinaka with 40 km range and guided missiles like Prithvi, which can strike at 250 km to 350 km range.” Related news items reflected that the Prahaar system “can tackle multiple targets and allows a mix of different kinds of missiles to be used from a single launcher. “Prahaar can hit a target 50-150 kilometres away,” read the short report in the Economic Times. The available information on the flight test of Prahaar leads to seven main inferences:

One, since the Director-General (DG) Indian Artillery Lt Gen. Vinod Nayanar was specially mentioned in the statement, it indicates that Prahaar may be inducted into the Indian army’s field artillery formations. That opens the inherently risky proposition of this weapon system’s control falling into the hands of junior commanders, delegative command and control and associated risks of inadvertent or un-authorised use. While the concern over command and control risks regarding Nasr remained exaggerated, surprisingly, no analyst has referred to such an obvious risk relating to Prahaar. Two, the DRDO worked in complete secrecy and in collaboration with the national industry for almost two years, which shows effective civil-military-industrial synergy and cooperation. More importantly, the development time span clearly shows that India did not develop Prahaar as a reaction to Nasr. India was already developing its short-range ballistic missile even if Pakistan’s Nasr had not come to the fore.

The flight test on 21 July 2011 three months after Nasr also suggests that development of Prahaar was not at a very successful or advanced stage. The flight test was initially planned on 18 July but was delayed till 21st, probably due to technical reasons. The video footage of the test shows that the flight test was done on an overcast day, thus precluding the option of not testing on 18 July due to weather limitation. Like Prithvi I (liquid-fuel missile), Prahaar (solid fuel) may still have technical glitches to overcome. Three, since the missile has a maximum range of 150 kilometres and can be deployed even in snow-bound areas or jungles; it can also be deployed against China. If deployed against its 3,380-kilometres border with China, it may provoke Beijing and add to the arms race in short-range ballistic missiles too. If India decides to deploy Prahaar against China, it would require a large number of missiles. It will, nevertheless, have sufficient fissile material to make the required number of warheads thanks to the pressure relieved on its domestic sources by several civil nuclear energy cooperation deals as well as the ‘recently discovered’ uranium mines in Andhra Pradesh that started production in December 2011.

Four, due to Pakistan’s geographical shape, Prahaar can engage both counter-force and counter-value targets. Likewise, Prahaar’s range is identical to Prithvi-I. Hence, it can be argued that Prahaar is a solid-fuel-Prithvi I. Five, since the missile can be launched within a few minutes, it would give the Indian forces good reaction time and quick launch options. If India decides to delegate the control to junior leaders in the battlefield, it will further telescope the decision time and the senior leadership will have little time to reverse the decision.

Six, though the Prahaar weapon system allows a mix of different kinds of missiles to be used from a single launcher, only one missile was fired on 21 July. Hence, more tests would be required to check weapon systems’ performance once all missiles are simultaneously fired in multiple directions. The reason that some DRDO scientists suggest attempts to reduce the missile-weight points that launcher will be more manoeuvrable once the load is reduced. Seven, Dr. Saraswat was intentionally vague about the time Prahaar would reach the production-ready status. If the timeline of the induction of Prithvi-I missile is any guide, it may take up to seven years before Prahaar is actually handed over to the ground forces. Given the complexities involved in developing multi-barrel capability, Prahaar would take even longer than Prithvi-I. Seven, specifying minimum range as 50 kilometres is significant in the sense that a vertically fired missile can fall back at the launch site too. This becomes more important as some Indian missiles have failed at launch in the past.

The 50-km minimum limit could be interpreted that the system would be deployed in a way that it is 80-100 kilometres away from the target. Besides, the 50-km limit also indicates the safety distance that would be kept between the Indian troops and the ground zero of the very low-yield explosion. This argument can be extended to ascertain the yield of warhead and device type. The warhead for Prahaar-type SRBMs can be an enhanced radiation (neutron) bomb. This can be understood from the excerpt of an online source, which offers the following information on the yield and destruction capacity of a 0.01-kiloton bomb:

The smallest warhead at present capable of providing significant tactical effort is .01 KT (10 tons). Deriving its effect from neutron and gamma radiation it produces loss of co-ordination in 1 minute (death in 36 hours) against troops in the open up to a distance of approximately of 70 yards. It can be fired with safety at a distance of 600 yards from our own troops.At 1 KT (1000 tons) the same effect as above can be sustained up to a radius of nearly 400 yards while the safety distance increases to 1,500 yards. If the information on minimum range is juxtaposed to Prahaar, it can be inferred that India may be using neutron bombs atop Prahaar missile which would leave the structures intact and kill only the humans within 36 hours and keep the effects localised.

It may be recalled that the US reversed its development of neutron bombs because there were protests over their employment in Europe these would kill humans and retain the structures.(39) A high-energy neutron warhead (atop) Prahaar would theoretically allow India to use it against mechanised forces in an area the Indian forces would want to use for further ingress into Pakistani territory. A fission bomb, due to its blast effect, would render the territory impassable.