By Naziha Syed Ali

Brahmdagh Bugti, in an interview with Swissinfo in July 2015, said that Pakistan regarded him as “the most dangerous person since Osama bin Laden”. Indeed, in a US embassy cable dated Feb 26, 2010 and published by WikiLeaks, his name was among those listed among Pakistan’s “Most Wanted”.

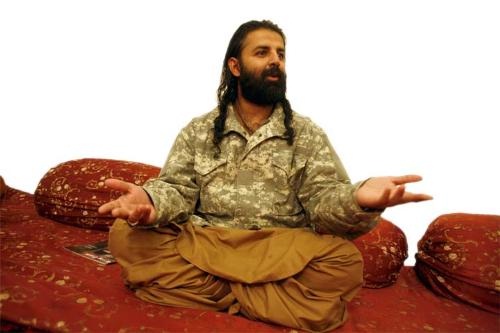

The grandson of Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti, who heads the Baloch Republican Party (BRP) from self-exile in Switzerland, has been uncompromisingly opposed to negotiations with the Pakistan government or any option short of Balochistan’s secession since he fled the country following the senior Bugti’s death in a military operation in 2006.

His interview to the BBC on Wednesday, in which he said he was willing to conditionally give up the demand for Balochistan’s independence thus created considerable stir in political circles. While the government has welcomed the development, the Baloch Liberation Front, the outlawed insurgent group led by Dr Allah Nazar, has expressed its disapproval. It has, however, chosen its words carefully, perhaps reluctant to annoy a scion of the powerful Bugti tribe. Also read: Brahmdagh’s statement a breakthrough: Balochistan CM

Several factors, both internal and external, have played a role in Mr Bugti’s about-turn. Journalist Shahzada Zulfiqar believes that international pressure is one of them. “Pakistan has for some time been approaching Western governments with the argument that they should not shelter people who are committing acts of terrorism in Pakistan,” he said.

The outlawed Baloch Republican Army (BRA), one of the major insurgent groups operating in Balochistan, is believed to be the militant wing of the BRP. On Jan 24, 2015 the BRA bombed two electricity transmission lines in Naseerabad district which plunged much of the country into darkness.

A changing regional environment also has a bearing on how Western governments respond to Pakistan’s strategy vis-à-vis Balochistan. “Proxy war pressures are easing in the region,” said Yousuf Mastikhan, a Baloch politician who was a member of the Grand Jirga that met in the aftermath of Nawab Bugti’s death. “Central Asia, Turkey, Iran and Pakistan need to work together. Even where Afghanistan is concerned, Pakistan has been attempting to nudge the Taliban towards talks.”

Diplomacy aside, military operations in Balochistan have also been considerably ramped up, thereby challenging the insurgents’ comparatively limited capacity. With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in the pipeline, securing peace in the province is considered an imperative and there have been reports of widespread destruction and casualties as a result of operations by the military.

Among the areas where alleged insurgents have been targeted and killed is Dera Bugti. “For the Bugtis, the stakes are particularly high because of Pakistan Petroleum Ltd’s presence in their area,” said Mr Zulfiqar. “Brahmdagh Bugti’s supporters who were employed at the Sui gas fields lost their livelihoods not to mention jobs in the Levies, the police and various government departments when they decided to support him so there was pressure building on him on that score too.”

Then there has been the well-publicised spectacle of insurgents laying down their arms before the authorities, although the veracity of these claims is disputed. “No doubt some rebels, including commanders, have surrendered, but many of them are those who had either surrendered a year ago when there was no amnesty in place, or they had already been expelled from their organisations,” said a journalist. “Nevertheless, it is demoralising for those in the field.”

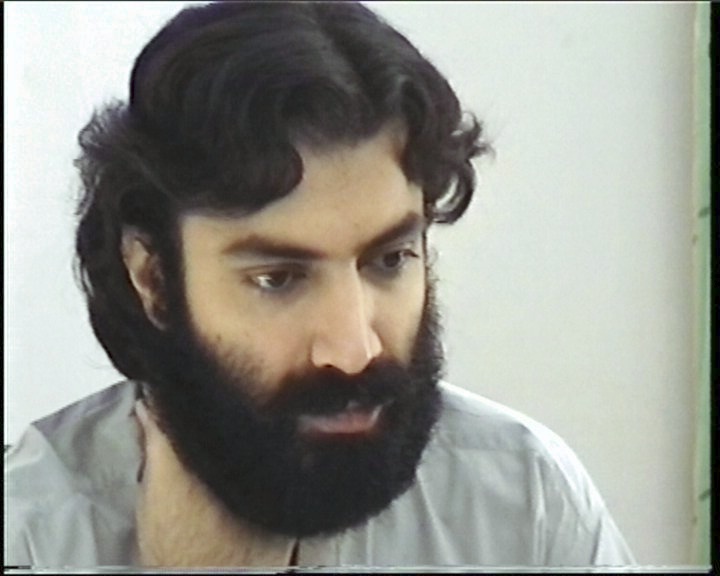

Internal crises over resources and strategy have also weakened the separatist movement which until recently formed a fairly united front; the areas in which various groups operate often overlapped. While it is possible that Mr Bugti’s statements to the BBC could exacerbate the rifts, some observers see his words in a different light. “As long as they are associated with the Baloch struggle, these leaders are a symbol of resistance,” maintained Mohammed Ali Talpur, a veteran of the insurgency from the ’70s. “The moment they take a decision to put down arms, they become individuals. Many people are not happy with Brahmdagh’s words.”

If the conditions Mr Bugti has listed are examined however, even those who are optimistic would have to concede there are serious challenges ahead. In the interview with the BBC he made the offer of rescinding his demand for an independent Balochistan if the Baloch people so desired.

Moreover, he said he would enter into negotiations with the government provided the military operation was stopped and the forces withdrawn.

“The army won’t stop operations; they think they have defeated the separatists who should now surrender; they think in black-and-white,” said Mr Mastikhan. “There has to be some face-saving for the separatists. Otherwise this will just be the lull before the storm. The government should negotiate with a political agenda in light of the Instrument of Accession signed by the Khan of Kalat in 1948, and determine what it can offer the Baloch short of independence.”

The state, if it is serious about capitalising on the opportunity offered by Mr Bugti, must rethink its approach. “The province is ruled by a colonial security structure that excludes the Baloch almost entirely. Even an ordinary protest by the Baloch is conveyed as a campaign for independence by the Frontier Corps [the federal paramilitary force deployed in Balochistan], and the next day troops are sent into that area,” said former senator Sanaullah Baloch.

“This trust deficit between Balochistan and the state must be addressed on a priority basis. We know the military has major strategic interests in the province, but these should not trample the interests of the Baloch.”

Courtesy Dawn