Within hours of winning the May 2013 elections, Nawaz Sharif made a point of meeting with Indian journalists who had been covering the campaign. He told them that, as he looked ahead to his third term in power, improving relations with Delhi was one of his top priorities.

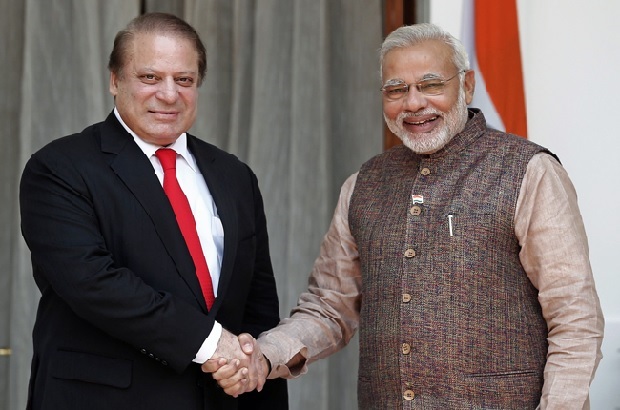

A year later, when Narendra Modi stormed to victory in India, he seemed to have similar ideas and immediately invited Nawaz Sharif to Delhi. It was the first time a Pakistani leader had attended an Indian prime minister’s inauguration ceremony.

The atmosphere of positivity even penetrated Pakistan’s military. The high command in General Headquarters in Rawalpindi has an unshakable, deep distrust of India. Even so, some senior officers argued that Mr Modi’s reputation as a hardline nationalist might enable him to take risks in delivering some kind of deal to end India and Pakistan’s differences.

But a year and a half later the two countries’ officials can’t even agree to meet, never mind move towards a settlement. Meanwhile the Pakistani and Indian armies are exchanging fire across the line of control in the disputed territory of Kashmir. The optimism has gone.

Mumbai ‘insult’

From India’s point of view the reason is clear enough. Even if Islamabad is now confronting the Pakistani Taliban, it has not shown any sign of moving against Lashkar-e-Taiba (now renamed Jama’at ud Dawa), the militant group suspected of carrying out successive operations in India including the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

Indeed, the man accused of masterminding Mumbai, Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, walked free from a Pakistani jail in April this year. A spokesman for India’s interior ministry described Lakhvi’s release as “an insult to the victims of the 26/11 Mumbai attack”. Since then the two countries have traded accusations.

In June, on a visit to Bangladesh, Narendra Modi accused Pakistan of promoting terrorism in India. For its part, Pakistan accuses India of providing support to separatist insurgents in Balochistan and to violent political activists in the county’s commercial capital Karachi.

Talks abandoned

Despite all the public rancour, when Mr. Modi and Mr Sharif met at the sidelines of a conference in the Russian city of Ufa this July they tried to start a dialogue process. The two men agreed that their national security advisers should meet to discuss, among other things, ways to expedite the Mumbai trial.

But Pakistan backed out of the talks hours before they were due to begin. It’s widely assumed in Pakistan that the military – which traditionally controls key foreign policy issues – told the government in Islamabad to abandon the dialogue unless the Kashmir issue was clearly on the agenda. Ever since 1947 both India and Pakistan have claimed that they should control Kashmir.

Decades of artillery exchanges, skirmishes, incursions, full-blown wars and a sustained insurgency have failed to alter the territorial share: Pakistan has around one-third of Kashmiri territory and India two-thirds.

More failed initiatives

Nawaz Sharif’s desire to improve relations with India goes back a long way. He also searched for an agreement in 1998 during his second term in power. That initiative was fatally undermined by the decision by Pakistan’s army to cross the line of control during the Kargil conflict.

Kargil war

- Conflict erupted after India launched air strikes against Pakistani-backed forces that had infiltrated Indian-administered Kashmir in May 1999

- Fighting built up towards a direct conflict between the two states

- Tens of thousands of people were reported to have fled their homes on both sides of the ceasefire line

- Both sides claimed victory in the conflict, which ended when, under pressure from the US, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif called upon the infiltrating forces to withdraw

- Later that year, General Musharraf led a military coup in Pakistan, deposing Mr. Sharif

Subsequent peace initiatives have also failed.

When General Musharraf tried to strike a deal in 2001, the Indian government rebuffed his efforts. President Asif Ali Zardari’s idea of improving trade links ran into opposition from entrenched business interests who benefit from the current stand-off. Pakistani security officials have watched Mr Modi’s growing confidence on the international stage with dismay.

The Indian leader’s nationalist politics, coupled with the size and potential of the Indian market, means that Islamabad’s campaign to win international support for its case over Kashmir looks more forlorn than ever. Relations between Delhi and Islamabad are also undermined by the situation in Afghanistan.

Privately Pakistani officials justify their support for the Afghan Taliban by saying they need a powerful, friendly force in Afghanistan to counter growing Indian influence there. Narendra Modi and Nawaz Sharif may both want to settle their countries’ differences. But there is little sign of them being able to do so.

‘Courtesy BBC News’.