By Brigadier (R) Mehboob Qadir

It was Mid 1972. We had just arrived in Ranchi from Agra, badly shaken and bruised, after a fateful train journey, during which we lost a fellow officer, killed by an armed escort needlessly, and another missing. Earlier, we had been declared most dangerous PoWs after our attempt to escape from the Agra Jail had been aborted; as a result we were bundled off to Camp 95 Ranchi. We were prepared for the expected hardships; not that it would have been unusual, but in the business of war, such turns for the worse are perfectly understandable.

As we arrived, we were counted and ushered into rooms in fives and sixes. In Ranchi, our eyes could see as far as our sight could. It had its own set of flying, crawling insects, families of slithering greenish-yellow grass snakes chasing agile jungle mice. Ranchi was lush green in all its lovely hues; from dark green groves of palms swaying in gentle breeze to golden green tea-gardens, carpeting endlessly, undulating slopes of low hills, right into the crystal blue horizon. Grass was like Shanghai velvet soft, lustrous, dense, which seemed to change hue with each little gust of wind that grazed past.

The rains lasted from March to November; close to 750 inches of rain poured down. Sometimes clouds arrived from as many as three different directions almost simultaneously with an amazing precision. I have hardly ever seen such a mesmerizing spectacle anywhere in the world. By evening, our towels used in the morning would catch fungus due to the intense humidity.

Our leather boots began to stink, twist and soon became unusable. Humbler Hawaii slippers turned out to be the best and more hygienic footwear along with equally practical khaki shorts and sleeveless vests. Another little discomfort was the itchiness in the folds of the body that soon turned into oozing, itchy sores. It was a result of excessive humidity and our ignorance about how to prevent Tinea (a skin condition).

Those suffering had to apply a pinkish, creamy fluid, and let the spots sun-dry, which used to be quite an unabashed scene at sunrise the perimeter guards’ right to privacy and decent exposure notwithstanding. One could understand their embarrassment, but the medical necessity prevailed over our natural reluctance. The camp was part of the British-built Ranchi Cantonment but located on a remote limb. Ours were quite frugal barracks with reasonable rooms and attached washrooms. There was a simple but central mess hall and kitchen.

The windows were duly barred and doors locked from the outside after the evening head count until the morning. Ours was the last room, temptingly close to the wire fence from where the forest belt was only a stone’s throw away. Beyond that was the road to Patna. Soon some of us buried ourselves deep into Red Cross-provided books; others turned toward religion and a few remained disoriented and bitter to the end.

Subedar Doongar Singh was our Camp JCO and our link to the camp administration. Lean, dark, of medium height and a face-in-the- crowd type. But what a tremendous human being dutiful, utterly uncomplicated, friendly, sensitive. These traits were not a result of expediency of the moment, as many might think, but very naturally a part of his character, as I was to learn later under some very trying conditions.

An infantry soldier of the regular Indian Army, he belonged to the fertile Rohtak-Hissar region. Like Central Punjabis, Rohtakis are very earthy and fearless people. They speak an interesting mix of Punjabi and Urdu dialect, laced with frank but unprintable words. Their sense of humor is highly contagious.

At the start of every month, I was supposed to compile our demands for knickknacks like toothbrush, shaving cream, soap and blades,etc, that we could obtain out of our 90 rupees monthly allowance and hand over to Singh. Soon, we developed a working relationship, which turned into an equation that has propelled me to write about this extraordinary man with 40 years in between.

Cash and valuables like watches and rings had been taken from us and were strictly prohibited. One day, he caught me caressing my engagement ring that I had hidden with great effort and ingenuity, but he showed extraordinary sensitivity to let me keep it when told why I had not turned it in, saying, “Sahib, God bless you. She must be a very bhaagvan kanya (fortunate girl).” The real test of his mettle came during a winter night, quite unexpectedly.

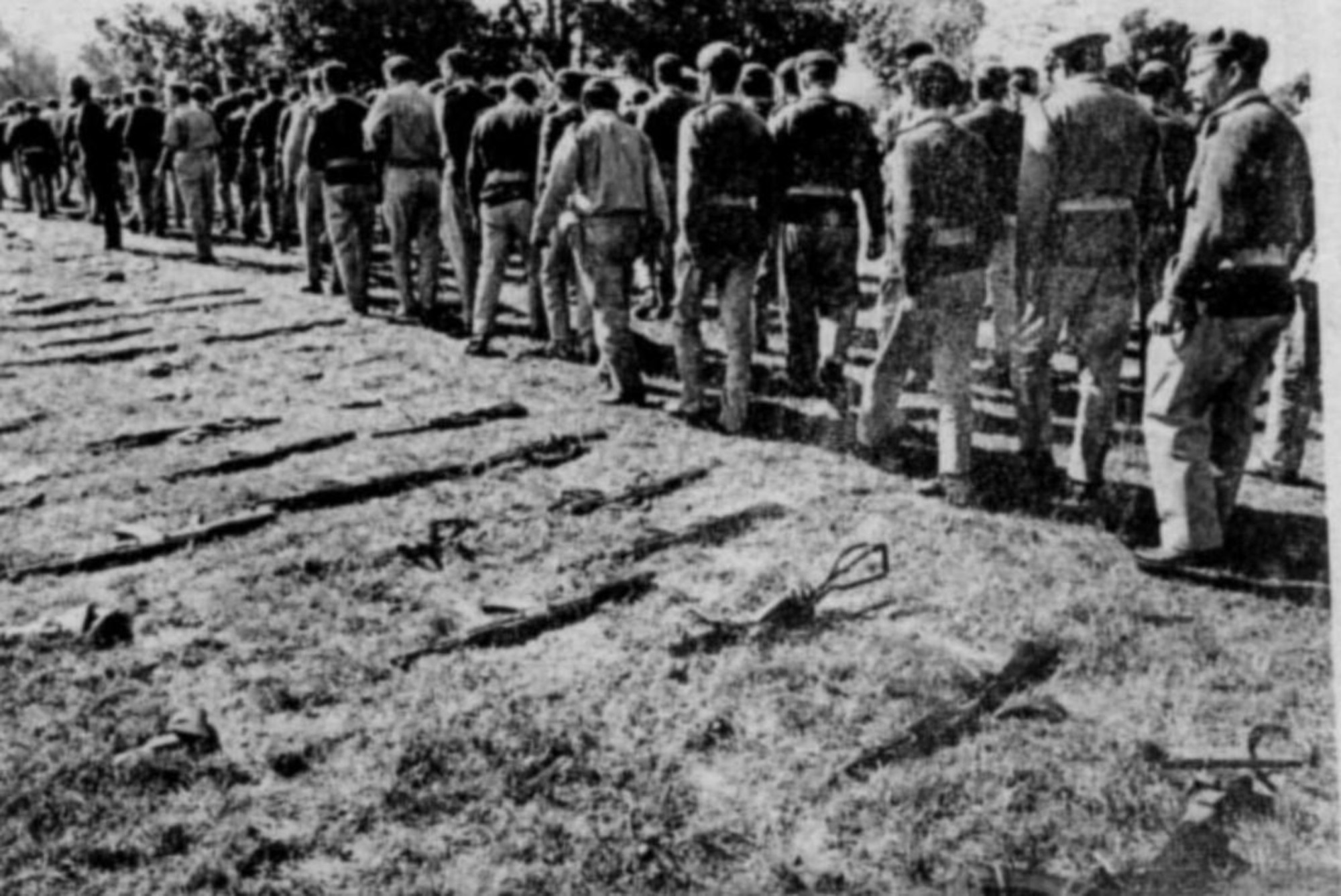

We had begun to dig a tunnel under the floor of our room during the nights. Our ‘lookout’ man would sit close to the window from where the only gate into the Camp was visible and was at a five minutes’ distance. I had just finished my digging turn when there was a powerful knock on the door. The lookout had probably dozed off. There was real panic.

With lightning speed, we covered up everything and feigned sleep before opening the door. Camp administration probably had a tip or suspicion; therefore, our room had been raided directly. We were ordered out; I quickly grabbed my ring and stood outside for a head count and body search. At that moment of anxiety and confusion, I felt a slight touch on my shoulder in the dark. It was Singh. I knew why. I thought for a moment and then slipped my ring into his palm. The search was soon over and the raiding party moved away, along with Singh. I was wide-awake that night. The ring’s weight in gold was immaterial, but it was an object of belonging in that terrible adversity.

Doongar Singh reappeared next morning with a mischievous smile on his face. Again, I knew why. He said, “I know you people are determined and would do some chamatkar (remarkable deed); that is why you people have red eyes in your barracks while others don’t.” He took out a crumpled piece of paper from his pocket and quietly returned my ring wrapped inside it. This kind of courage is rare and touching, sterling humanity. He used to distribute ICRC delivered letters from home to the officers himself.

As time passed,he got to know the names, classes and interests of the children of married officers. It was amazing to see him discuss their progress and related matters so intimately as if talking about his own family. He had an endearing habit of earnestly consoling those who sometimes did not receive a letter on the mail day.

In the course of captivity, I got my turn to return a bit of his kindness one day. I found him quietly sobbing, sitting in his favourite corner of our enclosure. Hearing me approach, he tried to wipe his tears, but in vain. He was inconsolable as I placed my hand on his shoulder and kept it there for a long time. I did not say a word. I felt fortunate at being there for him. His teenage daughter had died suddenly and he could not make it to her last rites.

Victorious or defeated, human sentiments are universally the same. Grief pains and happiness pleases without exception. When repatriation to Pakistan started finally, Doongar Singh was beside himself. He was passing through two different and mutually exclusive states of mind, both stemming from his natural make up.

As the first batch of POWs left, tears welled up in his eyes, which he tried to control with great effort. He was struggling to put up a brave smile but with faintly quivering lips. Happy to see us go but sad to lose us, he explained. What a marvellous human being he was. May his goodness be rewarded and bliss increased many times more, over and again, wherever he may be. He made our days in the most unusual way.