By Michael Kugelman

Abdul Sattar Edhi was his country’s greatest living hero. Here’s hoping that his legacy persists in the hands of a new generation of humanitarians. In May 2002, police discovered the mutilated body of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Karachi, Pakistan.

When it was time for Pearl’s remains to be collected and prepared for the long trip back to the United States, the police who found the body didn’t undertake this delicate task. Neither did any other law enforcement official or public servant.

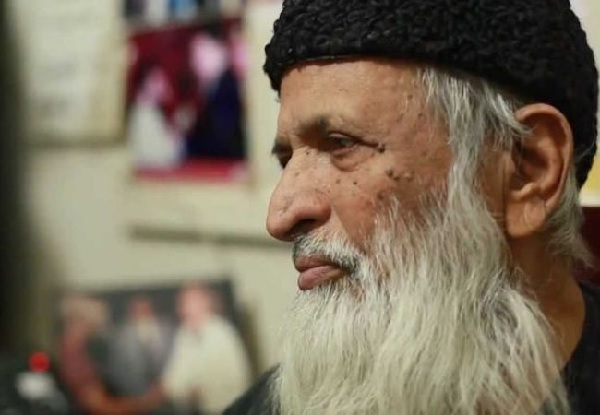

Instead, the task fell to a white-bearded elderly charity worker named Abdul Sattar Edhi. He “gently collected the body parts, all ten,” National Geographic reported five years later, “and took Daniel Pearl to the morgue.” On July 8, Edhi, Pakistan’s and possibly the world’s greatest humanitarian, passed away in a Karachi hospital. The cause of death was renal failure. He was 88.

Edhi’s death triggered an outpouring of grief across Pakistan. He received a state funeral, an honor the country had not accorded in nearly 30 years. Pakistanis are calling for a national holiday in his honor, and for stadiums and airports to be renamed after him. Countless encomiums have appeared in the Pakistani press in recent days.

This deeply respectful posthumous treatment is befitting for arguably the most widely admired person in Pakistan the man who revolutionized philanthropy and social work in the country. Edhi’s fellow Pakistanis routinely bestow upon him honorifics rarely heard anywhere in the world: living saint, angel of mercy, even Father Teresa.

Such admiration is easy to understand. For 68 years, nearly the length of Pakistan’s entire existence, Edhi’s life served a singular and sublime purpose: to help as many people as possible, with no questions asked and no expectation of reward or recognition.

In 1948, not long after partition drove his family out of Gujarat in present-day India and into Karachi, then the capital city in the country that would become his home, he cobbled together the funds to purchase an old station wagon, which he refashioned into an ambulance. At barely 20 years old, he set up a modest medical facility, and slept on a bench outside so that he could immediately receive anyone arriving in the middle of the night.

In the succeeding years, Edhi and his wife Bilquis would develop the Edhi Foundation, a sprawling yet remarkably efficient welfare organization that now provides medical care, ambulatory services, schools, orphanages, and facilities for the mentally ill, drug addicts, and victims of domestic violence. Its work also extended abroad, assisting the needy across the world, including in the United States.

The stories that Pakistanis tell about Edhi have made him a living legend. He owned just several articles of clothing. He slept in his office and always traveled in an ambulance so that he would be ready, at any second, to aid those in need. He placed cribs outside his foundation’s offices so that unwanted babies could be left in his care instead of simply abandoned.

As a result, 20,000 people in Pakistan now list Edhi as a parent or guardian, in a country where the state can’t provide care at that volume. And he never accepted a single donation from the Pakistani government. As a matter of principle, he only took private donations.

During his final days, Edhi refused offers to go overseas for treatment. He insisted that his eyes one of his few remaining working organs be donated. And, immediately after his death, they were to two blind people. His last words were reportedly: “Take care of the poor people in my country.”

What endeared Pakistanis to Edhi was not just his prodigious philanthropy per se, but also the critical purpose it served providing basic services that were otherwise in desperately short supply. According to one estimate, there is only one doctor for every 18,000 people in Pakistan.

Public ambulatory services are sparse and shoddy; one provincial health minister has suggested that ambulances have been used for shopping expeditions instead of emergency response. At least 4 million orphans live in Pakistan, according to estimates, yet there are few national laws or policies to help them.

Epidemics of heroin and meth, among other drugs, are ravaging Pakistan, yet counter narcotics officials peg government spending at just four cents per addict annually. In the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa alone, according to a 2014 estimate, there are nearly 2 million drug users, yet only 17 treatment facilities. And some 25 million Pakistani children do not attend school.

The Edhi Foundation addresses all these needs, thereby filling an enormous vacuum left by an overburdened and absentee state. In Pakistan, however, Edhi is revered not just for what he did, but for what he represented. He reflected aspects of the nation often overlooked overseas, where Pakistan’s image is far from stellar which upsets Pakistanis to no end.

Additionally, his work represented a lifelong act of defiance against Pakistan’s deeply entrenched afflictions. In a dangerously divided nation, he dared to deliver aid to anyone who needed it, regardless of sect or ethnicity. In a country cursed by vast levels of inequality, and where ruling elites have never made sustained efforts to uplift the masses, Edhi was un-apologetically pro-poor and anti-rich.

“The rich have deprived the people of their rights, and the state does not take responsibility for their welfare,” he declared in a 2011 Washington Post interview. “It is my dream to build a welfare state in Pakistan.” And in a society riven by extremism, Edhi publicly shrugged off threats from religious militants angered by his refusal to prioritize the care of Muslims over that of religious minorities.

Edhi was a unique figure in Pakistan. Islamist extremists aside, he attracted few enemies a rare feat in a nation often unkind to its heroes. Some of Pakistan’s greatest figures from schoolgirl Malala Yousafzai (dismissed by some Pakistanis as a tool of the West) to Nobel Prize-winning physicist Abdus Salam (disparaged for being a member of the minority Ahmadi Muslim community) have been shunned or maligned.

Also, in recent years, some of Pakistan’s most prominent national heroes have emerged only in death. Recall Aitzaz Hasan, the courageous teenager killed in 2014 when he tackled a suicide bomber outside his school and saved scores of lives. He posthumously received Pakistan’s top award for bravery.

And then there is Edhi, who was revered for his heroic deeds in life and will be in death as well. When alive, he was described as Pakistan’s only true living hero. In reality, Pakistan has always had living heroes, but few if any as well known and widely admired as Edhi.

To pay attention to the work of these other living heroes would help ensure that Edhi’s legacy lives on. We should focus on those who embody Pakistan’s rich tradition of charity and humanitarianism. These unsung heroes include Parveen Saeed, who runs a business that provides a full meal for three cents to anyone wishing to eat; Syed Fahad Ali, who manages a group of schools for the poorest of the poor in Karachi and other Pakistani cities; as well as young people in Lahore who spend their Sundays collecting garbage. They’re not as accomplished as Edhi, but they’re no less deserving of recognition and praise.

Edhi’s death is a loss for Pakistan, but also for the world. He passed away at a moment when violence, ignorance, injustice, and discrimination all of which he deplored deeply are seemingly intensifying across the globe, including in the West. We need more Edhis in this world.

That’s all the more reason to highlight those in Pakistan, and beyond, who continue to carry out quietly the kind of work that made Edhi a living legend. Perhaps, in time, accounts of the work of these heroes can inspire new ones.

‘Courtesy Foreign Policy’.