By Ahmed Rashid

In late 1994 and much of 1995 I would stand outside the Kandahar residence of Mullah Mohammed Omar, leader of the newly formed Taliban movement, hoping to secure an interview with him.

I came to know his drivers, secretaries, bodyguards, commanders and even his food taster (he feared being poisoned). I learnt a great deal about Omar but he never gave me an interview. While in power he refused almost all meetings with foreigners and it was a rare Taliban fighter who knew what he looked like.

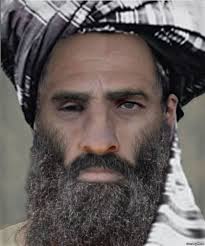

According to senior Taliban he was shy and reclusive, refusing to be photographed or leave any other record for posterity. There are doubts about the authenticity of the few pictures in the public domain said to be of him. Under his regime, television, films and images of people and animals were all banned.

The initial humility of this simple village preacher was striking. To issue orders to his commanders he sat on the cement floor of the governor’s mansion in Kandahar. Later, he promoted himself to a rickety string bed while supplicants sat on the floor. Eventually Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaeda leader killed in 2011, built a lavish bombproof house for him. Omar communicated through orders written on slips of paper. His signed chits allowing me to travel from city to city were at first written on wrapping paper or cigarette packets.

His naivety allowed him to be charmed by Bin Laden, to whom he gave sanctuary in 1996. Even after 9/11 he refused to give up on the al-Qaeda leader and as a result lost his country in 2001 to a US invasion. He was not seen in public after the attacks but it was presumed he spent the years before he died in Pakistan.

His death, announced by Kabul last week, was kept as much of a secret as his life . In recent days Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Taliban have tried to scrape together a credible story, since Omar is now believed to have died two years ago, aged about 56, in a Karachi hospital. The truth is out there but when everyone lies its difficult to see through the murk.

Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) was his protector first in the city of Quetta and then in Karachi, according to Taliban leaders and western diplomats. Pakistan itself appears reluctant to admit that Omar is dead.

A select few Taliban figures, including new leader Mullah Akhtar Mohammed Mansour, aged about 50, knew about his death but did not tell their comrades. He and others close to Pakistan are trying to hide this subterfuge by claiming Omar died just a few days ago.

It is not surprising Mullah Mansour has been hastily chosen as the Taliban’s new leader, as he was in contact with Omar when he was alive (and, after his death, he faked messages in his name). Yet many field commanders view him as an opportunist. Already Omar’s eldest son and others have denounced him, and demanded a full sitting of the leadership council to vote in a successor. For his part, Mullah Mansour has given a defiant acceptance speech, calling for unity in the ranks and saying the jihad war will continue against Kabul.

ISI and its Taliban protégés did not want to upset the status quo and risk a power struggle within the Taliban something that is happening anyway

Some Afghan officials in Kabul certainly suspected that Omar had died but they stayed silent. In recent months other radical groups close to the Taliban such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Feday-e-Mahaz, a hardline breakaway group have said that he was dead. Western embassies in Kabul presumed the same.

So why the silence from so many? ISI and its Taliban protégés did not want to upset the status quo and risk a power struggle within the Taliban something that is happening anyway. The Pakistan military’s recent positive change of policy on combating terrorism at home and pushing for peace talks between Kabul and the Taliban needed the stabilising presence of an illusory Omar in charge.

In Afghanistan, politicians who suspected the Taliban leader’s death feared the aftermath, particularly the possibility of a more extreme Taliban or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (known as Isis) gaining ground.

Mullah Mansour will not find a smooth path. Taliban talks with Kabul, due to start on in Pakistan on July 31, have been postponed. Some Taliban, tired of their leaders’ lies, may join Isis.

The best outcome for Afghans would be for the majority of Taliban to join the peace process promoted by Kabul and Islamabad. But that is unlikely now. Ever present is the threat of an emboldened Isis rushing to fill the void.

A peaceful outcome is still possible. For its part, Pakistan needs to act wisely and fairly by encouraging all Taliban to the table rather than just its protégés. But never underestimate the Afghan capacity for emerging from the shadows only to plunge straight into another war.

Courtesy The Financial Times