His beginnings in the army were not very propitious. His difficulty sprouted from the beard he sported which, especially an untrimmed one of the ‘suchi’ definition, was not as common as it is today. When he refused to part with his beard despite repeated admonitions by his company commander, he was produced before the battalion commander, Lt Col Akhtar Hussain Malik (later Lt Gen). As Saadullah waited outside his office, the company commander went in with the charge sheet, and recommended to the Colonel that the cadet should be withdrawn from PMA for the offence of gross insubordination and refusal to obey a lawful command. “What is his offence?” asked the Colonel. “His failure to shave off his beard sir, despite being ordered to shave it off many times.”

“But that is no offence. And have you already told him that he is to be withdrawn?” “Yes sir,” replied the company commander sheepishly. “Well, if anyone needs to be withdrawn, it is you. You do not know the regulations on the subject, and you have embarrassed me in the process. Anyhow, call him in.”Saadullah marched in. “So what is this problem with your beard Saadullah?” asked the Colonel, without the slightest inkling of what he was in for. “I have no problem with it sir,” replied Saadullah, “but everyone else seems to have an issue with it. What I cannot understand sir is that all the early Muslim generals had beards, and within less than a hundred years they conquered half the world. And here I am, just a lowly cadet in a Muslim army, and my beard seems to have become a source of contention for all those around me!”

“Indeed” replied the Colonel after a few moments of reflection, “these Muslim generals did conquer half the world in a very short time, but let me assure you that their beards played no part in these conquests. They would have made their conquests with or without their beards. Besides, we are in the Pakistan Army of today. Look around you, and see the emphasis on uniformity. Just look at your uniform and mine. Except for the ranks we wear our attire is identical. Just examine your boots and how your laces are tied, and then have a look at mine and you will not be able to point out any variation.

I like my cadets to stand out, but you are standing out because of your beard, which in my opinion is not a good enough reason to stand out. But anyhow, that is your business. Let me tell you though, that you are well within your rights to sport a beard and I will make certain that this matter is never brought up again. I will also officially record this incident, so that even if I am posted out, this matter may not be agitated again. Now you are free to leave.”

Gentleman Cadet Saadullah Khan marched out of the office of his Commanding Officer, went straight to the barber’s shop and got his beard shaved off. A year later Lt Col Akhtar Malik was transferred from PMA to take command of 2/16 Punjab Regiment at Chaman on the Pak-Afghan border. A year or so after that Saadullah Khan passed out of PMA with the Sword of Honour. This gave him the privilege to opt to be commissioned in any unit of the Pakistan Army. He opted for Lt Col Akhtar Malik’s unit.

Regimental service

After a number of stints in the unit, and other staff and instructional appointments, he was promoted to the rank of Lt Colonel in mid-1966 and transferred to take command of 2/16 Punjab Regiment in Lahore since renamed 14 Punjab. He was a hard task master, driving himself the hardest, setting the highest standards of command, and always leading by example. For instance, during summer collective training in the enervating July and August of Lahore weather, he never used commanding officer’s privilege of using a jeep, but always marched with his unit. He emphasized the need for every officer to know the names of all their men and know about them as much as possible, because in the end it was men who won battles, and not weapons. When he was transferred out after two years of command, he knew the names of most of the eight hundred men in his unit. He was a stickler for discipline, but only for the spirit that underlay discipline.

Thus whenever he gave orders or instructions which were not run-of-the-mill military orders, he explained the rationale, so that those who had to carry it out, were vested in carrying it out well. He was a great adherent of the principle that if anything was worth doing, it was worth doing well. And he was a great believer in the average person’s abilities, which he believed could be honed to perfection provided the commitment was there. And it was this commitment, he believed, which was the job of a commander to create among his subordinates. On matters of discipline, he was always forgiving if he felt he saw genuine remorse. But he never could forgive conduct he saw as dishonourable. His own nephew was serving in the unit under him. But when he thought that the escapades of this young officer were all too frequently crossing the line from youthful misadventure to the unacceptable, he had no qualms having him thrown out of the army.

Saadullah was a great believer in self-improvement. Thus he was very well read on a whole variety of subjects. But where he was quite unique was that he was an unlikely combination of a practicing Sufi and a die-hard soldier but never let the one intrude upon the other. For example, no one, except in the privacy of his home, ever heard him ask for a ‘jainamaz’, or which way the Qibla was, or if it was time for a certain prayer yet, etc, etc. Indeed no one ever saw him pray, while everyone knew that this man never missed a prayer, not even Tahajjud! The only place where Saadullah’s deep religious convictions showed, was when confronted with lies, no matter what rank the source of such lies may hold. He believed it was downright sinful to assent by greeting with silence, a proposition one deeply disagreed with. At times like these Saadullah spoke up and registered his disagreement. Very correctly, very politely, but this had to be done.

Legendary war performance

The year 1971 saw him in command of 27 Brigade in East Pakistan. The period after the military crackdown starting in March 1971 witnessed unforgivable atrocities from Bengali militants and occasional outburst by own soldiers. For someone like Saadullah, a complete soldier-patriot on the one hand, and a total believer in justice and a sensitive, practicing Sufi on the other, the emotional conflict can only be imagined. His answer was to carry his court martial box in his jeep and dispense summary justice to anyone under his command accused of any crime or wrongdoing against the local population. He never allowed anyone to commit any sort of violence except treating the militants according to the law. A practicing Sufi who was well versed in the writings, poetry, and philosophy of ancient Sufi saints, Saadullah was largely a quiet and private man.

However, he was prone to explode and take direct action against anything or anyone he thought was bringing the Pakistan Army into disrepute or disregarding the Sufi code of ethics he had weaved for himself. Maybe it was this code that also elevated his reputation of being among those Pakistani military officers in East Pakistan who were deeply respected by Bengali civilians. He laid down a strict zero-tolerance policy for the men under his command and immediately admonished and punished any soldier under him who was found guilty of being involved in any atrocity against the Bengali civilians. Throughout the very trying days of the unfortunate civil war in East Pakistan Saadullah neither lost his humanity nor his nerve and continued to provide leadership to all those serving under him, and remained a great example of commitment and courage to those around or above him.

Leading from the front

His real test came when the Indian Army invaded East Pakistan and conventional operations began in December 1971. His Brigade was deployed in defense of Meghna Bridge, holding Ashuganj. On the morning of December 9 he was alerted about the possibility that an undetermined number of Indian troops had infiltrated to the rear of 27 Brigade’s defenses. While on the way to check out the situation for himself, and well short of where the infiltrators had been sighted, he came across a few of his troops who had taken up firing positions on an embankment, facing towards the rear of the brigade’s defenses. The Brigadier stopped his jeep and went over to them to find out what they were doing there. They told him that just over the embankment there were enemy soldiers.

When he crawled up and looked over the embankment, he was stunned to find that indeed there were Indian soldiers no more than 150 yards on the other side. He was expecting that the enemy infiltration effort had reached no deeper than the outskirts of Ashuganj. But on the present evidence the enemy had clearly outflanked his positions and was already in the town. He immediately called his wireless operator, jeep driver, office runner and a few stragglers up onto the embankment and started to engage the enemy with small arms fire. It was his assessment that though the enemy had come into Ashuganj, it was still in the initial process of deployment. He knew that if Ashuganj fell to the enemy that was the end for his brigade. He had a decision to make, and it did not take him long to make up his mind. He decided to attack the enemy immediately before he had time to fully settle. And he did attack with whatever number of troops he could collect without wasting a minute. In the event he could only muster less than a platoon.

Nevertheless, he formed them up, fixed bayonets and personally led the charge on the enemy troops closest to him. First the nearest sub unit of the enemy left its position and fled, crashing into the sub unit behind it, and taking it along in flight; and then another sub unit fled; and then another, till the Brigadier and his group, now reduced to six men, reached near the edge of Ashuganj town, with the enemy in full flight. At about this time he saw Maj Aftab about 400 yards behind him with two rifle companies of 33 Baloch who joined in the chase. After a battle lasting three hours Brigadier Saadullah now left the proceedings to Maj Aftab and left for his headquarters. In the event Maj Aftab saw every last one of the enemy killed or chased out of Ashuganj, and also captured eight enemy tanks in good running order.

A miracle had been wrought. Four Indian Infantry Battalions (10 Bihar, 2 EBR, 17 Rajput, and 18 Rajput) and one squadron of tanks had been chased out of Ashuganj by the bayonet charge of a Pakistani platoon led personally by its Brigade Commander, assisted later on by two of his rifle companies. For display of courage in face of the enemy, above and beyond the call of duty, Brigadier Saadullah Khan was recommended for the award of Nishan-e-Haider, Pakistan’s highest award for gallantry. No one was more deserving of it, perhaps ever. But there was not even a scratch on his body, so tradition disallowed it!

End of Indo-Pakistan war and its aftermath

The war ended in defeat for Pakistan, and this meant a POW camp for the Brigadier and so many other very gallant officers and men. After repatriation to Pakistan, Brigadier Saadullah Khan was approved for promotion to Major General in early 1973. Only the formality of signatures on the promotion order remained before he could wear the rank. Meanwhile there was a demonstration on ‘Assaulting across a Water Obstacle’ he had to attend, where the Corps Commander as the Chief observer. After the demonstration the officer who had arranged it, failed to ask the audience for their comments, and asked the Corps Commander if he would like to say a few words on what he had witnessed. As is usual, the General went ahead and praised what he had seen. After this, what the demonstration had depicted would have become a part of the army doctrine on the subject.

Brig Saadullah had had plenty of experience in real war situations of the sort of operation which was demonstrated. Just as the General finished his concluding remarks, Saadullah raised his hand and asked to be heard on the subject before the matter could be concluded. The General allowed him to proceed. In short, what Saadullah had to say was that should the just concluded demonstration become the basis of army doctrine on the subject, it would lead to mass slaughter of own troops without the enemy having to do much. He made it a point to stress that he was not talking about theory but that his observations came from practical experience of real battles in conditions which the demonstration sought to depict. The embarrassment on the General’s face was quite palpable. What should have been a happy ending for all, turned into a disastrous denouement of the event? This was to have telling effect on his career, rest is history. Thus the head of the finest Brigadier in the army, in the run for promotion to the next rank, was chopped off.

Admonishment and Sojourn into Balochistan

Saadullah lost little sleep over his supersession, nor did he have any time for it. Almost immediately afterwards his brigade was ordered to move to Balochistan to fight the insurgency there in the hindsight an admonition.

As was his wont and being a professional soldier, he drew every book on Balochistan from GHQ Library and moved to Balochistan as ordered. He had little doubt about how he would tackle the insurgency i.e., his primary goal was to win the hearts of the Balochis. Thus he laboured to find out the names of Balochi hostiles in his area of operations, and the hamlets or villages they belonged to. On every opportunity he got, he drove through these places. Following his jeep invariably were trailers full of rations which he personally distributed to the inhabitants, and asked them what more could be done for them.

Concurrently, he took skeletal medical team of his brigade to administer medical care to the locals. His reputation preceded him and the Balochi hostiles started to come down from the hills to surrender to him. They were always honourably treated. As the word got around, these numbers increased. Eventually, hostiles in areas of operation of other formations also started to come in to surrender to Brig Saadullah. This was a great achievement, but the envy it created was also great. For reasons hitherto unknown, one evening as he sat checking routine mail, he opened a letter informing him that he had been compulsorily retired “without the fault of the officer”, and that he must hand over charge of his brigade within 24 hours and doff the uniform to which he had brought so much honour. No reason was given. The date was February 14. Upon retirement Saadullah Khan went and devoted the rest of his life to the service of his ‘murshid’. The ‘sufi’ in him had at last subjugated the perfect soldier who had faded away. It is a pity that very few would know anything about this great man and his greatness. Seeds of greatness were in him right when he was a cadet and remained consistent in character all his life. A man who was a great leader of men and someone who liked to set the pace through self-example and from the front.

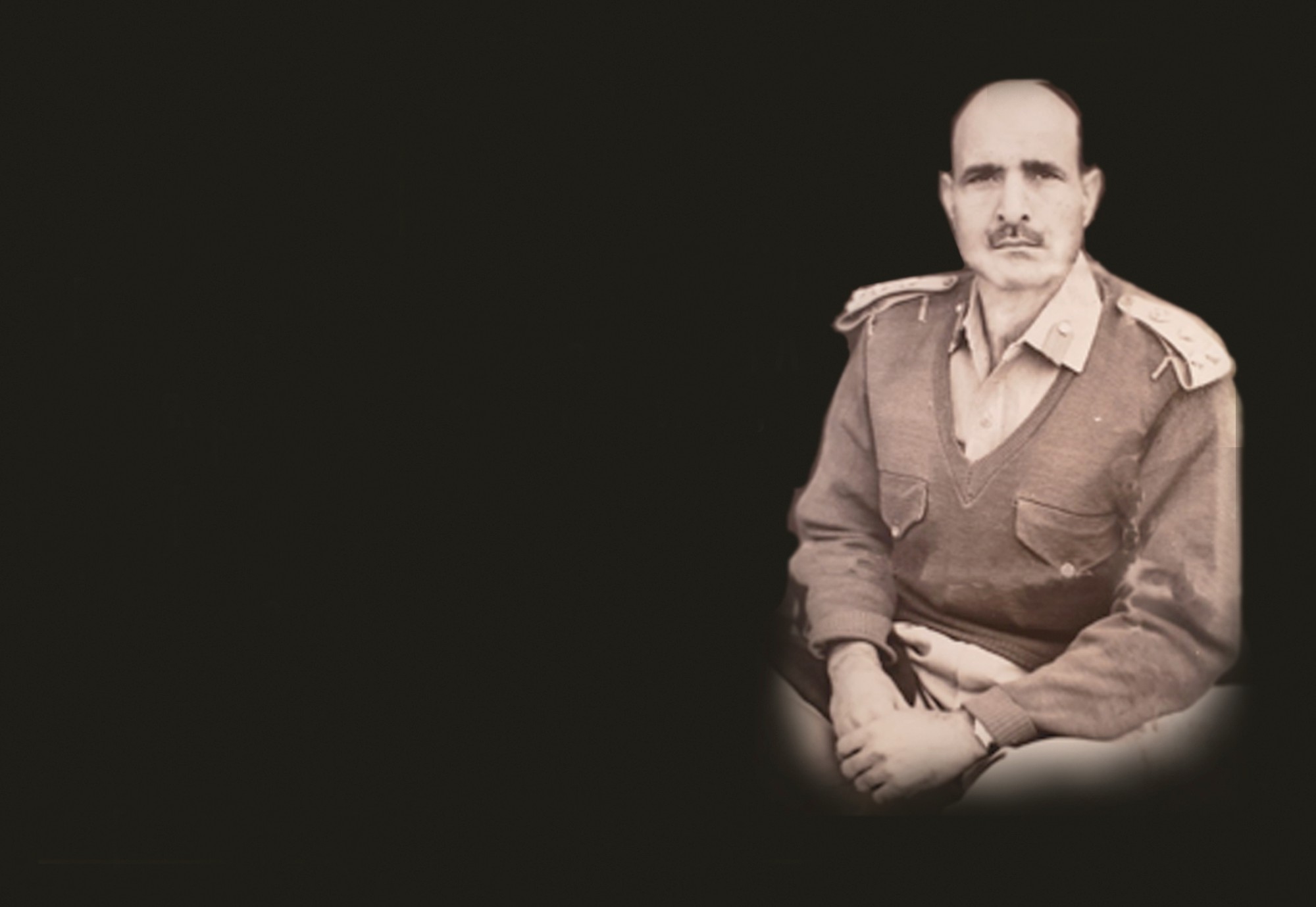

In the reckoning of many, late Brigadier Saadullah Khan is among the finest soldiers produced by the Pakistan Army.

The writer is a military historian and biographer.