Something is changing in the west’s relationship with Saudi Arabia. You can read it in the newspapers. You can hear it from politicians. And you can see it in shifts in policy.

Hostile articles about the Saudis are now standard fare in the western press. On Sunday, the main editorial in The Observer denounced the UK’s relationship with Saudi Arabia as an “unedifying alliance that imperils our security”. Two days earlier, the BBC ran an article highlighting an “unprecedented wave of executions” in Saudi Arabia. A couple of months ago, Thomas Friedman, arguably the most influential columnist in the US, labelled the terrorist group, Isis, the “ideological offspring” of Saudi Arabia.

Politicians are taking up similar themes. Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice-chancellor, has accused Saudi Arabia of funding Islamist extremism in the west and added: “We have to make it clear to the Saudis that the time of looking away is over.” In the UK, Lord Ashdown, a former leader of the Liberal Democrats, has called for an investigation into the “funding of jihadism” in Britain and pointed at Saudi Arabia.

The sudden increase in concern about Saudi Arabia is driven, in large part, by the rise of Isis. Western policymakers know that the battle with jihadism is as much about ideology as guns. When they look for a source of the Isis worldview, they increasingly trace it back to the Wahhabi philosophy promoted by the Saudi religious establishment.

Saudi influence in the west has also been weakened by other developments. The “shale revolution” in the US has made the west less dependent on Saudi oil. Meanwhile, the turmoil in the Middle East has shone a harsh light on Saudi foreign policy , with particular criticism aimed at the high level of civilian casualties caused by Saudi military intervention in Yemen, and Riyadh’s role in crushing an uprising in Bahrain in 2011.

For the moment, however, all this criticism has led only to modest adjustments in western policy. For the Saudis themselves, the most alarming change has been President Barack Obama’s determination to secure a nuclear deal with Iran, facing down fierce opposition from Saudi Arabia. Beyond the Iran deal, however, there have been only small, symbolic gestures, such as Britain’s decision, driven by human-rights concerns, to pull out of the bidding for a contract to provide training for prisons in Saudi Arabia.

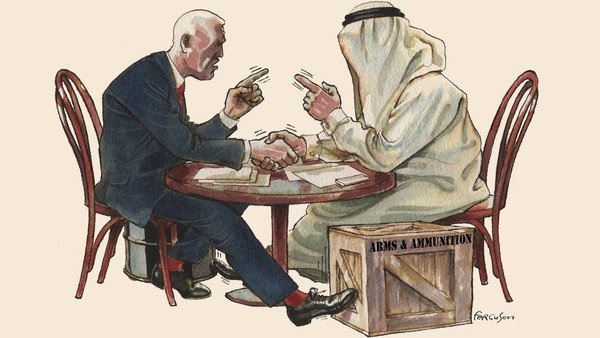

Over the past 18 months the US has approved the sale of more than $24bn of weaponry to Saudi Arabia Western critics of Saudi Arabia want to see the gloves come off. They accuse the governments of the UK and the US of being in thrall to Saudi money. Lord Ashdown has pointed to the influence of “rich Gulf individuals” in British politics. Saudi Arabia also remains a crucial market for western arms manufacturers. Over the past 18 months the US has approved the sale of more than $24bn of weaponry to Saudi Arabia.

There are also solid reasons, that have little to do with money, for continued western co-operation with Saudi Arabia. The past five years have demonstrated that when bad governments fall in the Middle East, they are often replaced by something far worse.